Preserving the Past: The Ancient Egyptian Practice of Mummifying Food

Ancient Egypt is famous for its elaborate burial customs and intricate beliefs about the afterlife. Among these customs, one intriguing practice stands out: the mummification of food. This fascinating tradition involved preserving and offering food items to the deceased, ensuring their nourishment in the journey to the afterlife. In this article, we'll explore the historical roots of this practice and delve into the tomb of the priestess Henutmehyt as an illuminating example.

The contents of King Tut’s tomb included 48 wooden boxes of meat mummies, stacked beneath a ritual couch that took the shape of a spotted cow.

The Ancient Egyptian Belief in the Afterlife

Ancient Egyptians had a profound belief in the afterlife, considering it an extension of earthly existence. In this belief system, the deceased were expected to embark on a challenging journey and needed sustenance, not only for their bodies but also for their souls. Food offerings were an integral part of ensuring a comfortable and prosperous afterlife.

The Origins of Mummified Food

The practice of mummifying food in ancient Egypt can be traced back over 3,000 years. It was a ritualistic process where various food items were preserved to serve the deceased in the next world. These preserved offerings were believed to maintain their freshness and taste, ensuring the continued well-being of the departed.

The Mummification Process

Mummifying food involved several steps, including drying and salting. By removing moisture and applying salt, food items were effectively dehydrated, preventing decay and spoilage. This preservation technique was akin to that used for human and animal mummies.

In a recent study, researchers have identified a remarkable ingredient used in an ancient preservation process: tree sap closely related to pistachios. This unique resin was generously applied to beef ribs before they were laid to rest alongside the great-grandparents of the legendary King Tutankhamun, dating back to approximately 1400 B.C. However, this wasn't just any ordinary substance. Imported from what we now know as Syria and Lebanon, this resin was a costly and exclusive material reserved for the elite and influential. When it made its appearance within funerary items, it took on profound symbolism, invoking a fundamental belief about the journey through death.

According to Salima Ikram, a renowned expert in mummies and an Egyptologist at the American University in Cairo, 'Once you were deceased and mummified, you ascended to godhood,' she explains. 'And these gods, in their divine form, inhaled the essence of these resinous substances.'

"The tomb of King Tutankhamun's great-grandparents, Yuya and Tuyu, yielded an array of resin-coated foods. When unearthed in 1905, the burial site still cradled the mummified remains of the two original occupants and some of their funerary possessions, despite having been subjected to multiple thefts in ancient times. Among the discoveries were 17 wooden containers, each intricately carved to depict the contents within—ranging from a leg of veal enrobed in linen to the shoulder of an antelope, alongside an assortment of three geese, two ducks, and possibly small birds believed to be pigeons. Yuya and Tuyu held the belief that these delectable offerings would magically reappear in the afterlife, ensuring their eternal sustenance."

Salima Ikram aptly refers to such ancient preserved meats as 'victual mummies,' a category she employs to classify beings intentionally preserved even beyond the threshold of mortality.

The Tomb of Priestess Henutmehyt

Another remarkable example of this practice can be found in the tomb of Priestess Henutmehyt, a noblewoman from the 21st Dynasty (around 1070-945 BCE). Located in Thebes, her tomb contained a variety of well-preserved offerings, including mummified food.

In Henutmehyt's tomb, joints of meat were found meticulously wrapped and preserved. These offerings were meant to ensure her sustenance in the afterlife. The mummified meat, wrapped in linen, was placed alongside other valuable items, such as statues and jewelry.

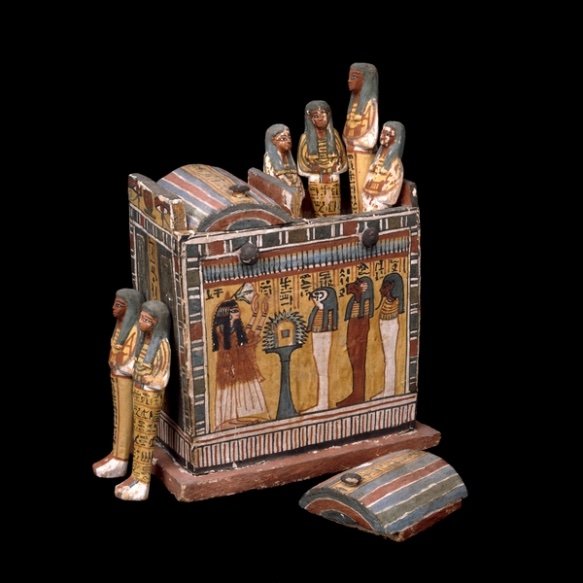

To assist in the provision of food, agricultural work, and other manual activities, tombs contained small statues called Shabtis. Their occupations were generally written on them, as can be seen in the following, which shows the shabtis of Henutmehyt.

The tomb of Henutmehyt provides a valuable glimpse into the importance of mummified food in Egyptian burial rituals. It reflects the depth of their belief in the afterlife and the meticulous care taken to ensure the deceased's well-being in the journey beyond.

Variations in Food Offerings

While Henutmehyt's tomb showcases mummified meat, food offerings in ancient Egyptian tombs could encompass a wide range of items, including bread, fruits, vegetables, and even beer. The selection of offerings often depended on the individual's social status, religious beliefs, and regional customs.

King Tut

The most extensive examples of 'victual mummies,' along with provisions for the afterlife, can be found in the illustrious tomb of none other than King Tut himself. Within the treasure trove of Tutankhamun's burial chamber, Howard Carter unearthed a tantalizing glimpse of the lavish feasts awaiting the young pharaoh in the great beyond.

Amid the treasures, over a hundred exquisitely crafted baskets cradled remnants of plant-based sustenance, including wheat and barley, freshly baked loaves of bread, succulent sycamore figs, sweet dates, luscious melons, and plump grapes.

Evidently, King Tut possessed a penchant for sweets. Carter stumbled upon a ceramic jar standing nearly eight inches tall, still bearing traces of a thick liquid that bore a striking resemblance to honey.

But Tutankhamun's indulgence didn't stop there. His collection also included jars brimming with wines, each meticulously labeled with the vineyard of origin, the name of the chief vintner, and the year of the pharaoh's reign when the wine was produced. Advanced scientific analysis confirmed that at least some of these wines were of the red variety.

As for meats, an impressive forty-eight wooden boxes housed a delightful assortment of 'victual mummies'—ranging from a variety of beef cuts still attached to the bone to an array of nine ducks, four geese, and various small birds. Strangely absent, however, were fish, despite the bountiful presence of fish in the Nile. 'The offerings are going to be the most high-class food, because this is for eternity,' explains Ikram. 'Fish are nice, but they don't make the cut for the eternal feast.' The same rationale extended to pork and sheep, meats that were part of the regular diet but seemingly lacked the enduring appeal needed for the eternal banquet.

'You have lovely pieces of poultry,' Ikram remarks, 'And beef—prime cuts with the juiciest, meatiest portions. Delectable slices that would make your mouth water. They'd focus on the legs to ensure they got the savory bits, not the tougher shins.'

In essence, these eternal picnics were meticulously packed with a gourmet wishlist—foods that the departed knew they'd relish for all eternity. 'Whether or not you indulged in these delicacies during your earthly life,' says Ikram, 'it didn't matter, because you were securing them for the hereafter.

Wrapping it Up (Get it… Wrapping …. because ahhhh well you know!)

The practice of mummifying food in ancient Egypt serves as a testament to the rich tapestry of their burial customs and religious beliefs. It underscores their deep reverence for the afterlife and the lengths to which they went to honor and provide for the deceased. I have to write, as a disclaimer here-although I think it’s obvious to those who follow me where my ethics and philosophy lies- that when it’s written in articles that these tombs had been robbed numerous times, and yet they don’t refer to British archeoligist as grave robbers too, that I am giving some serious side eye. I am grateful to their discoveries but anything that is a relic of Egypt belongs to Egypt and should be only lent out to museums for the benefit of Egypt. If you disagree, I mean we can’t cherry pick what’s right when it’s convenient to our colonial history. I don’t usually drop political conversation in my work but I think that we owe it to the countries we devour to discuss the ethics of, well anything that doesn’t belong to us, which is an awful lot.

Sources:

Packing Food for the Hereafter in Ancient Egypt

The Lunch Box of Priestess Henutmehyt, Her Eternal Workers, & Her Final Demise

Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation: The Howard Carter Archives