Hedy Lamarr: November 9, 1914 – January 19, 2000

The Obituary:

Hedy Lamarr; Screen Star Called Her Beauty a Curse

Hedy Lamarr, the raven-haired screen siren known for exceptional beauty that was described by Hollywood columnist Hedda Hopper as “orchidaceous,” was found dead Wednesday at her home in suburban Orlando, Fla. She was 86.

A Sheriff’s Department spokesman said Lamarr’s unattended death was being investigated as a routine matter and was not considered suspicious.

In her heyday, from the late 1930s to the early 1950s, she starred in 25 films, including “Algiers” with Charles Boyer, “Comrade X” and “Boomtown” with Clark Gable, “Tortilla Flat” with Spencer Tracy and John Garfield, and her greatest commercial success and first Technicolor film, “Samson and Delilah” with Victor Mature.

Whatever critics said about her acting or the public about her notoriety, her beauty was universally praised.

“My face has been my misfortune,” she wrote in her 1966 autobiography, “Ecstasy and Me.” “It has attracted six unsuccessful marriage partners. It has attracted all the wrong people into my boudoir and brought me tragedy and heartache for five decades,” she wrote. " My face is a mask I cannot remove. I must always live with it. I curse it.”

Unimpressed with roles in which she was required only to look pretty, Lamarr was often quoted as saying: “Any girl can be glamorous; all you have to do is stand still and look stupid.”

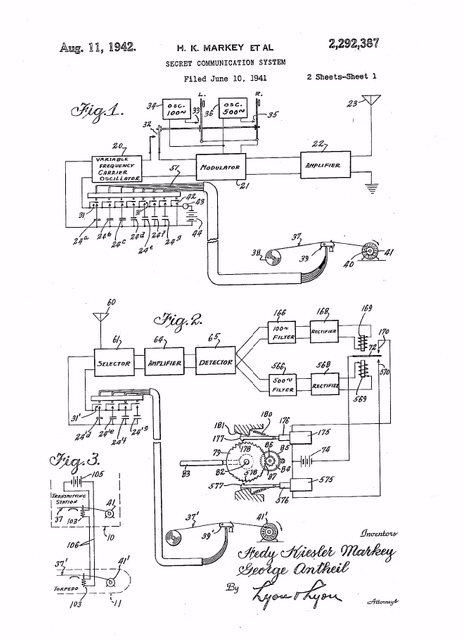

Far from stupid, she and composer George Antheil shared a patent issued in 1942 for inventing a technological system they called “frequency hopping.” It is still used in military communications.

But the woman who was once one of filmdom’s biggest attractions earned some unflattering headlines in her later years.

She was charged with shoplifting both in Los Angeles and near her retirement home in suburban Orlando. She also became quite litigious, suing the San Francisco Chronicle and the more flamboyant National Enquirer for libel when the Chronicle ran a picture of a two-headed goat named Hedy Lamarr and the Enquirer claimed that she had become “a pathetic recluse” and “old and ugly.”

Born Hedwig Kiesler, the daughter of a Viennese banker, young Hedy sprang into international attention at 17 when she performed some nude scenes in the controversial 1932 Czechoslovak film “Ecstasy.”

To Lamarr, the film was “a harmless little sex romp about a sweet young thing who marries an older man [who was] unable to consummate the marriage on the wedding night.”

To U.S. arbiters of taste, the film was legally obscene, and it was banned in this country for several years.

“The primary objection was not the nude swimming scene, which you have no doubt heard so much about, or the sequence of my fanny twinkling through the woods,” she wrote in her autobiography, “but the close-ups of my face in that cabin sequence where the camera records the reactions of a love-starved bride in the act of sexual intercourse.”

She claimed that the director tricked her into doing the nude scenes by moving the camera to a distant hill--then using a telescopic lens. She said he obtained her facial reactions by sticking her with a pin.

Lamarr’s first husband, Austrian munitions manufacturer Fritz Mandl, was unaware that she had done the nude scenes. He was horrified when the film appeared, and spent a fortune buying up every print he could find. His embarrassment, of course, helped make the film a classic.

Lamarr fled that marriage after three years, obtaining her first divorce in France.

“I couldn’t be an object,” she recalled in 1990 when she was 75, “so I walked out.”

Louis B. Mayer, who met her in London and signed her to a seven-year contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer during their Atlantic Ocean crossing, gave her the name that was to become famous.

She arrived in Hollywood in late 1937, brushed up on her English and was soon known as an exquisitely beautiful “exotic,” a mysterious foreigner who could play many ethnic roles.

Her first film, “Algiers,” according to then-Times Hollywood columnist Donald Hough, “established her as the No. 1 desert-island choice of the average American male.” But she continued to fight for more serious parts such as “Comrade X” in 1940.

“The word was passed,” Hough wrote then, “that this was no mere Viennese doll; this was somebody with brains and a sense of humor, perhaps with acting ability--certainly with determination.”

Although Lamarr didn’t obtain U.S. citizenship until 1953, she was fiercely pro-American during World War II, selling war bonds, washing dishes and dancing with men in uniform at the Hollywood USO canteen, and offering her new homeland her frequency invention to be used to direct torpedoes at moving ships.

The invention had its beginnings when the public was encouraged by the National Inventors Council to submit ideas for defense devices. Lamarr discussed her concept with Antheil when she met him at a party given by actress Janet Gaynor. On leaving, she scrawled her phone number in lipstick on his car’s windshield. The two met at her house the next evening to work out the technology.

Using knowledge gained from Mandl’s dinner table conversations with munitions customers, she helped Antheil diagram the communication system.

Ironically, the two Hollywood inventors earned nothing from their 1942 patent. The sophisticated anti-jamming device was not implemented by the Defense Department until 1962, when Sylvania installed it on ships sent to blockade Cuba. The patent had expired, with the rights to the invention falling into the public domain.

Lamarr never tried to promote her invention, considering it merely her contribution to the war effort.

When she was 75, she agreed to discuss the invention with Forbes magazine. She refused to pose for pictures, however, or grant a face-to-face interview. “I still look good, though,” she said by phone.

At the time of the 1990 interview, she was retired and living alone in a one-bedroom apartment in Miami, supporting herself modestly with a Social Security check and a Screen Actors Guild pension. She later moved to Alamonte Springs near Orlando.

Chiefly through lawsuits, Lamarr staunchly fought any image of her as a recluse in poverty in her retirement years. She was acquitted of shoplifting charges in Los Angeles, and charges that she stole eyedrops and laxatives in Florida were dropped after her promise that she would not break the law.

“I have no idea where my next meal is coming from, and some days I go hungry,” she told a curious fan without bitterness as early as 1965.

A year later in her autobiography she clearly stated her carefree philosophy about wealth: “I figured out that I had made--and spent--some $30 million. . . . I advise everybody not to save; spend your money. Most people save all their lives and give it to somebody else. Money is to be enjoyed.”

She took marriage more seriously than her string of six divorces might indicate. Twice she abandoned her career to move to husbands’ homes, in Mexico and Houston, and she never sought a major share of her husbands’ fortunes.

After her divorce from the industrialist Mandl, Lamarr married two Hollywood personalities: producer and writer Gene Markey, with whom she adopted a son, James Lamarr, and then actor John Loder. Loder adopted James and fathered her two other children, Denise Hedwig and Anthony (Tony) John.

When she married her fourth husband, Acapulco nightclub owner Ernest (Ted) Stauffer, Lamarr publicly sold much of the furniture and Hollywood mementos from her Beverly Hills home and moved to Mexico. But she claimed that Stauffer ignored her, when he wasn’t flying into jealous rages, and they separated after only six months.

Lamarr also moved to Houston, the home of her fifth husband, Texas oilman W. Howard Lee. That marriage lasted seven years, during which Lamarr made her final films, “The Loves of Three Queens” in 1954, “The Story of Mankind” in 1957 and “The Female Animal” in 1958. With Lee’s financial backing, she produced a film in Italy that was never released.

Lamarr also continued her hobby of painting, and hung many of her works in their sumptuous home.

But her efforts to fit into Houston society were frustrated, and she and Lee divorced in 1960.

Lamarr’s sixth and final marriage, to attorney Lewis W. Boies Jr., who was six years her junior, lasted from March 4, 1963, until their separation on Oct. 15, 1964, after several physical battles.

In addition to the six marriages, there were affairs along the way, with women as well as men.

“Yes, occasionally I have gone for a woman,” Lamarr wrote in her autobiography. “But not for love, only excitement and thrill. I have always preferred men to women.”

“In a way, I really had a nymphomania,” she reflected in her book. “I don’t believe man was made for one woman and woman for one man.”

Lamarr appeared to live her life on her own terms and without regret. She often joked about such flaws as her inability to choose good scripts. She had turned down “Casablanca,” for example, which became a hit for Ingrid Bergman.

“When I die,” Lamarr once told a friend, summing up her devil-may-care life, “I want on my gravestone: ‘Thank you very much for a colorful life.’ ”

The Recipe: Käsespätzle

Pasta Ingredients

3 cups + 1 tbsp all-purpose flour

1/3 cup semolina flour

1/2 cup potato flour (potato starch)

1.5 tsp olive or canola oil

1 tsp salt

1/4 tsp turmeric

2 cups + 2 tbsp soy milk

Cheese Ingredients

250 g potatoes

1-2 carrots

1 onion

2-3 garlic cloves

175 ml of the water from the cooked vegetables

80 g cashews (optional sub cashew butter)

3 tbsp nutritional yeast

1 tbsp lemon juice

1/2 tbsp mustard

1-2 tsp salt

1 tsp cayenne

Toppings Ingredients

5 onions sliced (you can use yellow or white)

500 g mushrooms

2 tbsp vegetable oil for frying (do not use olive oil)

salt and pepper to taste

vegan parmesan to garnish

Cheese Sauce Directions

There are a few different ways to prepare your cashews depending on your time requirements. You can soak them overnight and they will be good to go the next day when you are getting ready to make this. But, if you forgot to do that or are starving, you can simply place them in some boiling water for 10 minutes. I use a percolator and pour hot water over them, and then let them sit in a pyrex bowl. Whatever you choose to do, getting the cashews ready is your first step here.

Bring a large pot of water to boil.

While your water is boiling, chop up your potatoes, carrots, onions, and garlic. Don’t worry about how they look. The goal here is to make them small enough to boil and make super soft because later we are going to blend these veggies up to make a smooth creamy base for your sauce.

Add vegetables to boiling water and cook for 15-18 minutes. Basically you don’t want to remove these veggies until the potatoes are tender enough that they fall apart when pierced with a fork.

Remove vegetables with a slotted spoon and toss into a blender. Keep 175ml of the cooking water and add to blender with the vegetables. (Pssst that water? Congrats you just made vegetable stock so honestly I save all the water when I make this and use the remainder of the water later)

Blend vegetables, 175ml of cooking water, drained cashews, nutritional yeast, lemon juice, mustard, salt, and cayenne in the blender until you have a smooth creamy sauce.

I usually pour this back into the pot I had boiled the veggies in to keep warm while I am making my pasta. However you can toss it in a small saucepan if you are about to reuse the pot for your pasta.

Toppings Directions

Slice onions. We are going to fry these, so thin slices works best but for god sake don’t cut yourself trying to get the perfect slice.

Slice mushrooms.

Add 2-3 tbsp of vegetable oil to a skillet and carefully heat up.

Fry onions in the oil for 2-3 minutes.

Add mushrooms and cook for another 5-8 minutes until golden brown.

Set veggies aside as this will be the last thing placed on your pasta.

Pasta Directions

Fill a large pot with water and bring to a boil. We will be using this water to boil your noodles so you’ll want it at least 3/4 full to have enough water to submerge the pasta in it. Lightly salt the water. I just toss a pinch of salt in my water.

Mix all pasta ingredients in a large bowl and combine until a dough begins to form. It should be slightly liquidy and be able to drip off your spoon.

If you have a spaetzle press, use that to press your noodles into the boiling water. If you are like me and have no idea what that is, you can use a sieve to press the dough through that with the back of a spoon acting as your “press”.

As soon as the spaetzle rises in the water it means they are ready to be removed. Take a slotted spoon and scoop them out and then rinse under cold water to keep the pasta bits from sticking together.

Top with cheese sauce, caramelized onions, mushrooms, and parmesan.

Sources:

Oliver, Myrna: Hedy Lamarr; Screen Star Called Her Beauty a Curse, LA Times

Zapatka, Bianca: German Cheese Spaetzle, Bianca Zapatka